Digital Cameras When It Went Mainsteam?

For an inventor, the main challenge might be technical, but sometimes it'south timing that determines success. Steven Sasson had the technical talent just developed his prototype for an all-digital camera a couple of decades too early.

A CCD from Fairchild was used in Kodak'south first digital camera prototype

It was 1974, and Sasson, a young electrical engineer at Eastman Kodak Co., in Rochester, N.Y., was looking for a use for Fairchild Semiconductor'south new type 201 charge-coupled device. His boss suggested that he try using the 100-by-100-pixel CCD to digitize an paradigm. So Sasson built a digital camera to capture the photo, shop information technology, so play information technology back on another device.

Sasson'south photographic camera was a kluge of components. He salvaged the lens and exposure mechanism from a Kodak XL55 movie photographic camera to serve as his camera'due south optical piece. The CCD would capture the prototype, which would then be run through a Motorola analog-to-digital converter, stored temporarily in a DRAM array of a dozen iv,096-bit fries, and so transferred to audio tape running on a portable Memodyne information cassette recorder. The photographic camera weighed 3.half dozen kilograms, ran on xvi AA batteries, and was about the size of a toaster.

After working on his photographic camera on and off for a year, Sasson decided on 12 December 1975 that he was ready to take his beginning picture. Lab technician Joy Marshall agreed to pose. The photograph took near 23 seconds to record onto the audio record. Only when Sasson played it back on the lab reckoner, the paradigm was a mess—although the camera could render shades that were clearly dark or lite, annihilation in between appeared equally static. So Marshall's hair looked okay, but her face was missing. She took i wait and said, "Needs piece of work."

Sasson continued to improve the camera, eventually capturing impressive images of different people and objects around the lab. He and his supervisor, Garreth Lloyd, received U.Due south. Patent No. 4,131,919 for an electronic all the same photographic camera in 1978, just the project never went beyond the image stage. Sasson estimated that image resolution wouldn't exist competitive with chemical photography until quondam between 1990 and 1995, and that was enough for Kodak to mothball the project.

Digital photography took nigh two decades to have off

While Kodak chose to withdraw from digital photography, other companies, including Sony and Fuji, continued to move ahead. Afterward Sony introduced the Mavica, an analog electronic camera, in 1981, Kodak decided to restart its digital photographic camera try. During the '80s and into the '90s, companies made incremental improvements, releasing products that sold for astronomical prices and found limited audiences. [For a recap of these early efforts, see Tekla Southward. Perry's IEEE Spectrum commodity, "Digital Photography: The Power of Pixels."]

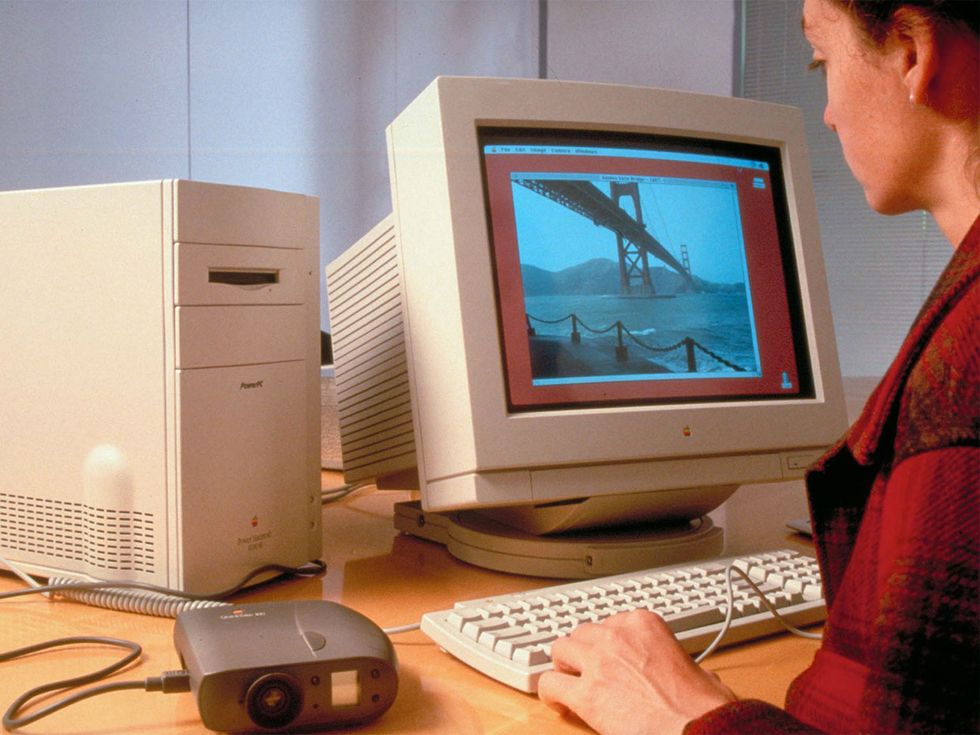

Apple tree's QuickTake, introduced in 1994, was one of the first digital cameras intended for consumers. Photos: John Harding/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

Apple tree's QuickTake, introduced in 1994, was one of the first digital cameras intended for consumers. Photos: John Harding/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty Images

So, in 1994 Apple unveiled the QuickTake 100, the showtime digital photographic camera for nether US $1,000. Manufactured by Kodak for Apple, it had a maximum resolution of 640 by 480 pixels and could but store up to eight images at that resolution on its retention card, but information technology was considered the breakthrough to the consumer market place. The following twelvemonth saw the introduction of Apple'south QuickTake 150, with JPEG image compression, and Casio'south QV10, the first digital camera with a congenital-in LCD screen. It was also the year that Sasson'due south original patent expired.

Digital photography really came into its own as a cultural phenomenon when the Kyocera VisualPhone VP-210, the first cellphone with an embedded photographic camera, debuted in Japan in 1999. Iii years later, photographic camera phones were introduced in the United States. The outset mobile-telephone cameras lacked the resolution and quality of stand up-lone digital cameras, often taking distorted, fish-eye photographs. Users didn't seem to care. Suddenly, their phones were no longer just for talking or texting. They were for capturing and sharing images.

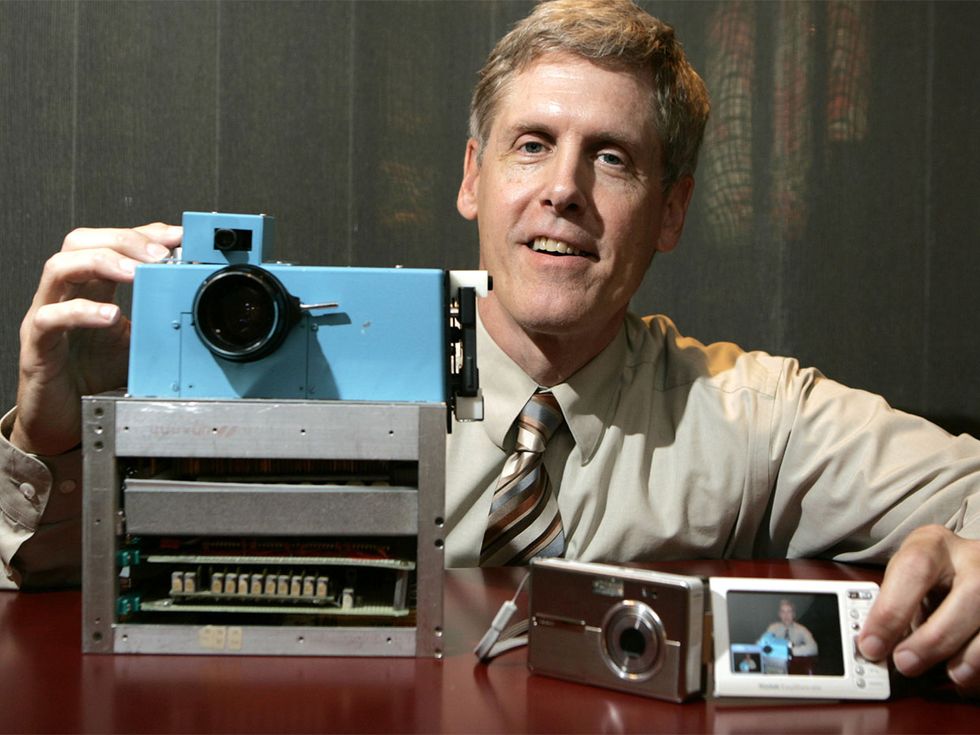

In 2005, Steven Sasson posed with his 1975 paradigm and Kodak's latest digital camera offering, the EasyShare One. Past then, camera cellphones were already on the rise. Photograph: David Duprey/AP

In 2005, Steven Sasson posed with his 1975 paradigm and Kodak's latest digital camera offering, the EasyShare One. Past then, camera cellphones were already on the rise. Photograph: David Duprey/AP

The rise of cameras in phones inevitably led to a refuse in stand-alone digital cameras, the sales of which peaked in 2012. Sadly, Kodak's early advantage in digital photography did not prevent the company's eventual defalcation, equally Mark Harris recounts in his 2014 Spectrum article "The Lowballing of Kodak'due south Patent Portfolio." Although there is still a market for professional and single-lens reflex cameras, most people at present rely on their smartphones for taking photographs—and and then much more.

How a technology tin change the course of history

The transformational nature of Sasson's invention can't be overstated. Experts estimate that people will take more than 1.4 trillion photographs in 2020. Compare that to 1995, the yr Sasson's patent expired. That spring, a group of historians gathered to study the results of a survey of Americans' feelings most the by. A quarter century on, ii of the survey questions stand out:

- During the last 12 months, accept you looked at photographs with family or friends?

- During the final 12 months, have you lot taken any photographs or videos to preserve memories?

In the nationwide survey of nearly 1,500 people, 91 percent of respondents said they'd looked at photographs with family or friends and 83 pct said they'd taken a photograph—in the by year. If the survey were repeated today, those numbers would nearly certainly be even higher. I know I've snapped dozens of pictures in the final week lone, most of them of my ridiculously cute puppy. Thank you to the ubiquity of high-quality smartphone cameras, cheap digital storage, and social media, nosotros're all taking and sharing photos all the time—last night's Instagram-worthy dessert; a selfie with your bestie; the spot where you parked your car.

So are all of these captured moments, these personal memories, a part of history? That depends on how you define history.

For Roy Rosenzweig and David Thelen, two of the historians who led the 1995 survey, the very idea of history was in flux. At the time, pundits were criticizing Americans' ignorance of past events, and professional historians were wringing their hands virtually the public'due south historical illiteracy.

Instead of focusing on what people didn't know, Rosenzweig and Thelen prepare out to quantify how people idea about the past. They published their results in the 1998 book The Presence of the Past: Popular Uses of History in American Life (Columbia University Press). This groundbreaking study was heralded by historians, those working within academic settings equally well every bit those working in museums and other public-facing institutions, because information technology helped them to think virtually the public's agreement of their field.

Fiddling did Rosenzweig and Thelen know that the entire subject field of history was about to be disrupted by a whole host of technologies. The digital photographic camera was just the beginning.

For example, a little over a tertiary of the survey's respondents said they had researched their family history or worked on a family tree. That kind of activity got a whole lot easier the post-obit year, when Paul Brent Allen and Dan Taggart launched Ancestry.com, which is now one of the largest online genealogical databases, with 3 1000000 subscribers and approximately 10 billion records. Researching your family tree no longer ways poring over documents in the local library.

Similarly, when the survey was conducted, the Human Genome Project was still years away from mapping our DNA. Today, at-home DNA kits brand information technology simple for anyone to order upwardly their genetic contour. In the process, family unit secrets and unknown branches on those family copse are revealed, complicating the histories that families might tell about themselves.

Finally, the survey asked whether respondents had watched a movie or tv show nigh history in the last year; iv-fifths responded that they had. The survey was conducted soon before the 1 January 1995 launch of the History Channel, the cable aqueduct that opened the floodgates on history-themed TV. These days, streaming services allow people binge-sentry historical documentaries and dramas on demand.

Today, people aren't merely watching history. They're recording it and sharing it in existent time. Recall that Sasson's MacGyvered digital camera included parts from a pic camera. In the early on 2000s, cellphones with digital video recording emerged in Japan and South Korea and then spread to the rest of the world. As with the early nonetheless cameras, the initial quality of the video was poor, and memory limits kept the video clips curt. But by the mid-2000s, digital video had become a standard feature on cellphones.

As these technologies become commonplace, digital photos and video are revealing injustice and brutality in stark and powerful means. In turn, they are rewriting the official narrative of history. A curt video prune taken past a eyewitness with a mobile phone tin can now bear more than authorisation than a government report.

Possibly the best mode to call up about Rosenzweig and Thelen's survey is that it captured a snapshot of public habits, just as those habits were about to change irrevocably.

Digital cameras also changed how historians behave their research

For professional historians, the appearance of digital photography has had other important implications. Lately, at that place'southward been a lot of discussion about how digital cameras in general, and smartphones in item, take changed the exercise of historical research. At the 2020 annual coming together of the American Historical Clan, for instance, Ian Milligan, an acquaintance professor at the University of Waterloo, in Canada, gave a talk in which he revealed that 96 percent of historians accept no formal training in digital photography and withal the vast majority utilize digital photographs extensively in their work. Near 40 per centum said they took more than ii,000 digital photographs of archival fabric in their latest projection. W. Patrick McCray of the University of California, Santa Barbara, told a author with The Atlantic that he'd accumulated 77 gigabytes of digitized documents and imagery for his latest book project [an aspect of which he recently wrote about for Spectrum].

And then let'due south recap: In the last 45 years, Sasson took his first digital picture, digital cameras were brought into the mainstream and then embedded into another pivotal technology—the cellphone and so the smartphone—and people began taking photos with abandon, for whatever and every reason. And in the last 25 years, historians went from thinking that looking at a photo within the past year was a significant marker of engagement with the past to themselves compiling gigabytes of archival images in pursuit of their inquiry.

The author's English Mastiff, Tildie, is eminently photographable (in the writer's stance). Photos: Allison Marsh

The author's English Mastiff, Tildie, is eminently photographable (in the writer's stance). Photos: Allison Marsh

And then are those 1.4 trillion digital photographs that nosotros'll collectively have this year a office of history? I retrieve it helps to consider how they fit into the overall historical narrative. A century ago, nobody, not even a scientific discipline fiction writer, predicted that someone would have a photo of a parking lot to recollect where they'd left their car. A century from at present, who knows if people will nevertheless be doing the aforementioned thing. In that sense, even the most mundane digital photograph tin serve as both a personal memory and a piece of the historical record.

An abridged version of this article appears in the July 2020 impress issue as "Built-in Digital."

Part of a continuing serial looking at photographs of historical artifacts that embrace the dizzying potential of engineering.

About the Writer

Allison Marsh is an acquaintance professor of history at the University of South Carolina and codirector of the academy's Ann Johnson Establish for Scientific discipline, Technology & Lodge.

Source: https://spectrum.ieee.org/how-the-digital-camera-transformed-our-concept-of-history

Posted by: clarkancentim.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Digital Cameras When It Went Mainsteam?"

Post a Comment